History

History  History

History  Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

10 Tragic Human Panics and Stampedes

The tragic loss of life at the Cambodia Water Festival on November 22, 2010, demonstrates how crowds can be uncontrollable and deadly forces.

Panics and stampedes can generally be broken down into two categories: acquisitive panics, where people rush headlong in a rush or panic to acquire something of value – say a better seat in a theater, or a chance to get that “must have” doll for a Christmas present when the shopping center doors open on Black Friday; and the typical image of a panic or human stampede – a life or death surge away from some form of danger – such as people trying to escape a burning night club. Both forms of behavior can lead to a human stampede and the deaths of scores, or even hundreds of people.

Though many panics do start as, or result in, a selfish, disordered or uncoordinated rush or push of people who are thinking only of themselves and their survival/needs – many human stampedes or crushes are also noted for the selfless and coordinated helping of others – those trying to calm the panic, people trying to help up those who have already fallen, or aid the weakest to escape the crowd.

One study of 215 stampedes, that took place over a 30 year period, showed that stampedes occur most frequently at religious events, with sports, political and musical events coming in close behind. Crowd size plays a role in the likelihood of a panic or stampede, but also many other factors such as whether the crowd is attending an organized event or has spontaneously gathered (such as for a political protest).

The prediction of the movement of people in a panic situation, what causes a crowd of humans to panic and how they react in a panic situation, and the dynamics of panics and stampedes, is still a developing science. But, as you will see, there are some common factors in many human stampedes.

On December 3, 1979, thousands of fans of the rock band The Who were waiting outside the entrances to Cincinnati Riverfront Stadium, on a cold December evening. The Who had not toured the USA for several years, and at every stop on their sold out tour fans were eager to see the legendary rock band. I was one of those fans, 20 years old, I was awaiting my first Who concert only a few nights later in Philadelphia, PA. Along with other Who fans, and those around the world, I was shocked at the images broadcast on TV that terrible night. In Cincinnati that evening, when the doors were opened, about 25 people were pushed to the floor of the concourse, only feet from the entrances. Of those, 11 fans were crushed to death.

The show went on that night without the band being told what had happened. The band was encouraged not to draw out the show and wrap things up. Upon going backstage, the members of The Who were told for the first time what had taken place. They were stunned and shocked.

This was a festival seating concert, as most concerts were then, first come, first serve of the available seats. After this tragedy, many concerts moved away from offering festival seating. No doubt the urge to get inside out of the cold weather, after hours of waiting, and eagerness to see the band (as well as to get a good seat) all played a role in what happened. The media portrayed the event as a classic rush of people pushing to get into the building so as to get good seats – and the concert goers as selfish barbarians and hooligans who, stoned on booze and drugs, trampled innocents like so many bugs. Those who were there described a different scene. Many observed others attempting to help those who had fallen, or who were struggling. Though the urge to enter the building to get a good seat was part of the tragedy (the acquisitive push), for those who were trapped and pinned at the doors by the force of the crowd behind them, once the doors were opened, reaching the safety of the doors and the open space beyond became a matter of life or death (the classic surge to safety).

More than 25 years later, on their 2006 album “Endless Wire”, Pete Townshend put into song the cold hard reality of what happened that night, and in other forms of “show biz” entertainment, in the song “They Made My Dream Come True”:

“People died where I performed

People cried when Glass deformed

Shots rang out as the singer yawned

The band played on until the dawn

Lies and drunks and drugs and fools

Tricks and stunts disguise the tools

Was the victim dead, was the blood in pools

Was this not part of show-biz rules?”

It is hard today to comprehend the momentous achievement that was the construction and opening of the Brooklyn Bridge. It was not only the longest and highest suspension bridge in the world, it also linked by foot travel, for the first time, the island of Manhattan to Brooklyn, over the East River. It was 1,600 feet long and towered 100 feet above the water. It took 14 years, cost $15 million and killed 20 workers before it was completed. But when it was done it soared like a colossus above New York City.

People thronged to the grand opening on May 24, 1883. On that single day an estimated 150,000 pedestrians paid the one penny toll to walk across it.

On May 30, 1883, the bridge was, as always, crowded with hundreds of people walking across, it when someone in the crowd shouted out “the bridge is collapsing!” Many in the public were still apprehensive of this gigantic and unprecedented construction of man, and when they heard this cry (untrue though it was), they believed it. In the resulting panic to get off the bridge, 15 people were trampled to death.

To later calm the public and show the bridge was indeed safe to cross, none other than PT Barnum would lead a parade of elephants back and forth over the bridge.

On July 24, 2010, a stampede occurred during the Love Parade electronic dance and music festival, in Duisburg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

The Love Parade has been a popular festival and parade that originated in 1989, in Berlin. However, this was the first Love Parade held in an enclosed and closed-off area. The capacity of the enclosed section was estimated to be 250,000, but there was anywhere from 200,000 – 1.4 million people attending the festival.

The festival was opened and people began to enter a tunnel which led from the east, and also through a series of underpasses which led from the west. Both met at a ramp that was supposed to be the only entrance and exit point of the festival area. A smaller ramp existed between the underpasses from the west. Because of overcrowding, police at the entrance began announcing over loudspeakers that new arrivals should turn around and head back. The side of the tunnel that was the entry of the parade area was closed, but people continued to enter the tunnel from the rear, despite being told it was closed. A stampede occurred as the ramp between tunnel underpasses and the festival area became overcrowded.

Witnesses claimed some people started falling off stairs and pulling others with them, and this caused the crowd in the tunnel to panic. Some felt falling was the cause of death, but autopsies showed that all of the fatalities were due to crushed rib cages.

Police did not cancel the festival that day for fear of causing another panic. However, the festival organizers say there will not be another Love Parade in honor of those who died.

On October 20, 1982, on a cold and snowy day a match was played between FC Spartak Russia and HFC Haalem, at what was then called Lenin Stadium (now Luzhniki Stadium) in Moscow, Russia. Because of the cold, few tickets to the game were sold, and only the east stands were opened for spectators. For security reasons, only one exit from the stand was left open. Just minutes before the end of the game with Spartak leading 1-0, people began to leave the stadium through this single exit. During injury time, Spartak scored its second goal. The player who scored this goal later said he wished he had never scored it.

Some of the fans who had left the stadium, hearing the crowd cheer the second goal, turned around to reenter the stadium and were met head on by the crowd still exiting. Guards would not allow those who were leaving to turn back and reenter the stadium. Somehow, a stampede broke out and many people were killed. One survivor described the stairs as slippery. As those exiting hit those trying to return, apparently some fell on the slippery surface. Those falling fell onto others, who fell onto others and a domino effect took place. The steel banisters on the steps collapsed. In the end, at least 67 people were killed, but survivors and family members claim the actual death toll to be as high as 340. As was typical of the Soviet Union at that time, hardly a word was mentioned in the news media about the tragedy, and it was not until 1989 that it was discussed in the open.

The history of the early 1900’s United States labor movement is filled with bloody fights and many deaths. One of the most tragic occurred on December 24, 1913, in Calmut Michigan when striking mine workers and their families were attending a mine union sponsored Christmas celebration on the second floor of the Italian Hall building. Over 500 people were thought to be in attendance that evening when someone shouted “fire!”

There was no fire, but one must remember the time period when this tragedy occurred. In the 1800’s and early 1900’s, people were deathly afraid of being trapped inside a building that was on fire. And for good reason – theaters and other public buildings would frequently catch fire, trapping those inside. Most everyone knew of one or more of the great theater fires of the time, such as the Iroquois Theater fire in Chicago only ten years earlier that killed 602 people. People were well aware that buildings were mostly fire traps made of wood that easily and quickly burned, and that most buildings, prior to fire safety laws, had few safe and reliable exits. Someone shouting “fire!” inside a building today would possibly get odd looks of disbelief from a crowd of people not accustomed to the hazards of building fires; people knowledgeable of various fire safety exits in all public buildings. But, in 1913, a crowd of people in a public building understood the danger of the word “fire” very well indeed, and reacted accordingly.

As was usually the case with these buildings, there was a single, narrow set of stairs leading out of the building. In the panic to escape the building which they believed was on fire, 73 people, including 59 children died in the crush.

No one to this day is certain who it was that yelled out “fire!”. The most common theory of was that a member of the company anti-union “goon squad” had been the person who cried out “fire!” in a crowded building. In fact shouting “fire!” in a crowded building would go on to become a popular US metaphor. In the 1919 case Schenck vs the United States, justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote an opinion from which the phrase “shouting fire in a crowded theater” has since come to be known as synonymous with an action that the speaker believes goes beyond the rights guaranteed by free speech, reckless or malicious speech, or an action whose outcomes are blatantly obvious. The phrase is used as an example of speech which serves no conceivable useful purpose and is extremely and imminently dangerous when used in this setting. Woody Guthrie would go on to immortalize the event in his song “1913 Massacre”.

On April 15, 1989, an FA Cup semi final match was played between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest, at the Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield England.

Because of many years of violent and disruptive fan behavior at British football matches (called “Hooliganism”) most football stadiums in the United Kingdom had been retrofitted with high steel fencing, to keep the spectators off the pitch and prevent them from throwing projectiles onto the field and at the players and officials. Because of these fences and security practices, UK stadiums had a history of crushes, including a major crush at the Hillsborough Stadium in 1981 when 38 people were injured.

As was standard security practice, fans for opposing sides were separated at different ends of the stadium. Nottingham Forest fans were placed in one end which had a capacity of 21,000, and the Liverpool supporters were placed at another end of the stadium, in an area which could only hold 14,600 fans. To make matters worse, many arriving fans had been delayed by traffic congestion. The match was scheduled to start at 3 PM but as late as 2:40 PM there were huge crowds of fans still waiting to enter the stadium in a small area at turnstile entrances. All were eager to get in before the match started.

A bottleneck developed, with more fans arriving than could enter the two cages set in the middle of the Liverpool fan side. The fans outside could hear the cheering from inside as the teams came on the pitch ten minutes before the match started, and again as the match kicked off, but could not get in; and the start was not delayed. With over 5,000 fans trying to push their way through the turnstiles, police realized a crush was imminent and so opened more gates to allow the crowd to enter. This led to a rush of fans into the stadium and a mass influx of thousands of fans through a narrow tunnel and into the two already overcrowded central pens. People at the front of the fence were being crushed by the force of those pushing to enter from behind. Those entering the stadium could not see this. Police who would normally have been stationed in position to see this and close the gates to stop the rush were not in position that day.

At first, no one noticed what was happening at the fence, but 3 minutes into the game the referee stopped the match as people started to clamber over the fence to escape the crush. A small gate in the fence was forced open and some were able to escape as more people climbed over the fence, and still others were pulled to safety by fans in the adjoining pens. Eventually the fence collapsed.

Those at the front of the fence were packed in so tightly many died standing up, suffocated to death by compressive asphyxia. A total of 96 people died and 766 were injured, making this the worst stadium disaster in British history, and one of the worst stadium disasters of all time.

What makes this stampede/crush so especially tragic is that all 183 victims were children, children between the ages of 3 and 14 years old.

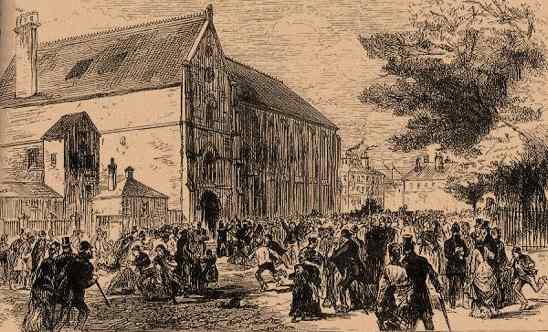

On June 16, 1883, a large crowd of over one thousand children had gathered for a show at the Victory Hall concert hall in Sunderland, England. Towards the end of the show an announcement was made that the children with special numbered tickets would receive gifts upon exiting the hall. Some entertainers began distributing gifts from the stage and the children, in a panic to get to the entrance and receive a prize, stampeded from the gallery to the bottom of the staircase. There, they were pushed into a small single opening through which only one child could pass at a time. In addition, the door swung inwards, towards the rush of children trying to squeeze through the one small doorway.

Children at the door were crushed by the force of those pushing from behind trying to reach the door. As the adults realized what was happening, they tried to open the door to allow more children to get through, but the door had been bolted on the children’s side and they could not reach it. A custodian managed to divert about 600 children to safety while other adults pulled children one at a time through the door. One man eventually pulled the door off its hinges. But it was too late to save the lives of 183 children who died from compressive asphyxiation. Outrage at this event led to changes in building design including the installation of outward swinging doors equipped with panic bars.

Occurring only days ago on November 22, 2010, the Phnom Penh stampede is yet another example of how crowds and bridges make for deadly combinations. As of the writing of this list, at least 465 are known to have died.

The tragedy took place towards the end of the three day Khmer Water Festival celebrations in the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh. The Water Festival is to celebrate the end of the monsoon season and the biannual reversal of flow of the Tonlé Sap river. Upwards of four million people attend the festival.

On the day of the disaster as many as 10,000 people had crowded onto Diamond Island, a small sliver of land on the river, to watch a boat race and enjoy a concert. In recent years, several people had drowned on the river during the celebrations and early reports say the authorities were focusing their efforts on preventing more deaths in the river and not on land.

The stampede occurred on the bridge across the river connecting the island to the main land. Authorities estimate as many as 7,000-8,000 people were on the bridge at the time of the stampede. The bridge was a suspension bridge and some theorize that those unfamiliar with such bridges did not realize that it is normal for suspension bridges to sway, and panicked when they felt the bridge moving, thinking it was about to collapse. Victims claimed they were trapped on the bridge for several hours even after the stampede occurred.

What started the stampede is not yet clear. Some reports state that people on both ends of the bridge started pushing, leading to a panic. Those in the middle of the bridge were pushed to the ground and trampled or crushed. Some claimed that those trying to escape the crush pulled down electrical wires and some victims were electrocuted, though this has not yet been confirmed. Another report claims the panic started when several people fell over, unconscious, on the crowded island. Still another report claims the panic began when the bridge began to sway back and forth. Another claim is that police fired a water cannon at the people on the bridge in an attempt to get them to disperse, but this too cannot be confirmed as of yet.

Some survivors claimed authorities had blocked access to a second bridge, forcing all to cross via the one remaining bridge.

Large crowds and bridges, as we have seen, do not mix. Once again, the two combined lead to tragedy. On August 31, 2005, around one million pilgrims had gathered around, or were marching toward, the Al Kadhimiya Mosque, which is the shrine of the Imam Musa al-Kazim, one of the twelve Shi’a Imams. To reach the shrine, pilgrims had to cross the Al-Aaimmah bridge over the Tigris river, located in Baghdad Iraq.

Tensions in the crowd ran high as earlier in the day a terrorist mortar attack on the crowd had killed several people. Many suspected another attack was imminent, possibly a suicide attack. One report stated a man pointed a finger at another, claiming he was wearing explosives, and this triggered the panic.

The resulting panic caused people to rush towards the bridge, which had been closed. A gate at the end of the bridge was opened and people rushed onto the bridge, trampling and crushing those who fell. At the other end of the bridge was a locked gate which could not be opened, and even if it could, it opened inward, towards the crowd pushing against it. Even more people were crushed against the fence by the force of the crowd pushing from behind. Railings on the sides of the bridge collapsed, sending more people hurtling 9 meters (30 feet) to the Tigris river below. Many could not swim and drowned, others drowned in heroic attempts to save them. At least 953 people were crushed to death or drowned.

The Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca in Saudi Arabia, known as the Hajj, has resulted in multiple stampedes and crushing deaths over the years.

As many as three million pilgrims arrive at Mecca each year, as those of the Muslim faith attempt to make at least one pilgrimage in their lifetime. For many, their first visit to Mecca would become their last.

With the advent of jet travel, more and more pilgrims than ever before can make their way to Mecca. Crowds have been increasing steadily for years. But the surging crowds, trying to make their way from one station of the pilgrimage to another, can cause people to be trampled if they fall down, and stampedes of people that trample even more.

The most dangerous part of the pilgrimage is the stoning of the devil ritual. Muslim pilgrims fling pebbles at three walls, called jamarat, in the city of Mina just east of Mecca. It is one of a series of ritual acts that must be performed in the Hajj.

To allow easier access to the jamarat a single tiered pedestrian bridge, called the Jamaraat Bridge, was built around them so pilgrims could throw stones from either the ground level or from the bridge. However, sudden crowd movements on or near the bridge can cause people to be crushed. On several occasions hundreds of participants have suffocated or been trampled to death in stampedes.

The bridge has been expanded in recent years to accommodate the ever-growing number of pilgrims, but because of the sheer size of the crowds the ritual is nearly impossible to control. Another safety measure was replacing the jamarat pillars with walls – which make easier targets to hit with the pebbles and speeds up the stoning.

But, even with these new safety measures, crowd control is still a serious problem. Crowd conditions are especially difficult during the final day of Hajj, when, according to hadith, Muhammad’s last stoning was performed just after the noon prayer. Many scholars feel that the ritual can be done any time between noon and sunset on this day; however, many Muslims believe they must perform the stoning immediately after the noon prayer. This leads to a mass rush of people wanting to do the stoning at one time.

The worst disaster took place in 1990, when there was a stampede inside a pedestrian tunnel and 1,426 people were killed. In 1994, a stampede during the stoning of the devil ritual killed 270. In 2004, 251 died during the stoning of the devil ritual. And in 2006, yet another 289 people died during the ritual.

During World War II, it was common for Londoners to shelter in London Underground (subway) stations. During an air-raid on 3 March 1943, hundreds of people attempted to enter Bethnal Green underground station in east London. A nearby unrelated explosion caused people to panic and a woman with a baby fell on the stairs down into the station, causing many others to fall and in 15 seconds 300 people were crushed in the stairwell, 173 fatally. However, no bomb struck and not a single casualty was the direct result of military aggression, making it the deadliest civilian incident of World War II in the UK. For wartime morale reasons it was not reported at the time.